[quote]Dark_Knight wrote:

Thibaudeau:

"Misunderstanding ‘Overtraining’

If you ask me, “overtraining” is the most abused and misunderstood concept in the entire strength training community! Perform more than twelve sets for a muscle during a workout and you’ll undoubtedly be accused of overtraining. Train a muscle group more often than two times per week? Overtraining! Relying on set extending methods such as drop sets, pre or post-fatigue, or rest-pause? What are you doing? Don’t you know that’s overtraining and you’ll shrink faster than your masculine pride on a snowy Canadian winter night?!

Yes, overtraining can eventually become a problem when it comes to your training performance, injury risks, and growth. However, it’s far from being as common as most people would have you believe.

The problem stems from the term itself, which is composed of “over” and “training.” Because of that term, individuals are quick to equate it to “training too much.” So every time someone thinks that a routine has too much volume, frequency, or advanced methods, they’re quick to pull the “overtraining” trigger. When someone is tired and has a few bad workouts he’ll also automatically assume that he’s “overtraining.” In both cases this shows a misunderstanding of what overtraining really is.

Overtraining is a physiological state caused by an excess accumulation of physiological, psychological, emotional, environmental, and chemical stress that leads to a sustained decrease in physical and mental performance, and that requires a relatively long recovery period. There are four important elements in that scientific definition:

“Physiological state:” Overtraining isn’t an action (i.e. training too much) but a state in which your body can be put through. In that regard, it’s similar to a burnout, a medical depression, or an illness.

“Caused by an excess accumulation of physiological, psychological, emotional, environmental, and chemical stress:” Stress has both a localized and a systemic effect. Every type of stress has a systemic impact on the body; this impact isn’t limited to the structures involved directly in the “stressful event.” This systemic impact is caused by the release of stress hormones (glucocorticoids like cortisol for example) and an overexertion of the adrenal glands.

So every single type of stressor out there can contribute to the onset of an overtraining state. Job troubles, tension in a relationship, death in the family, pollutants and chemicals in the air we breathe, the food we eat or the water we drink, etc. can all contribute to overtraining. Training too much is obviously another stress factor that can facilitate the onset of the overtraining state, but it’s far from being the sole murder suspect.

“Leads to a sustained decrease in physical and mental performance:” The key term here is sustained. Some people will have a few sub par workouts and will automatically assume they’re overtraining. Not the case. It could simply be acute or accumulated fatigue due to poor recovery management or a deficient dietary approach.

A real overtraining state/syndrome takes months of excessive stress to build up. And when someone reaches that state, it’ll take several weeks (even several months) of rest and recovery measures to get back to a “normal” physiological state. If a few days of rest or active rest can get your performance back up to par, you weren’t overtraining. You probably suffered from some fatigue accumulation, that’s all.

Worst case scenario, you might enter an overreaching state (a transient form of overtraining). Reaching that point will normally take 10-14 days of rest and active rest to get back up to normal. Overreaching can actually be used as a training tool since the body normally surcompensates (with rest) following overreaching. Elite athletes often include periods of drastic training stress increases followed by a 10-14 day taper to reach a peak performance level on a certain date.

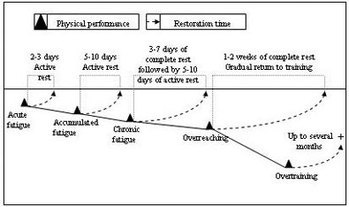

“That requires a relatively long recovery period:” As we already mentioned, reaching a true overtraining state takes a long period of excessive stress and requires a long period of recovery. The following graphic illustrates the various steps toward the onset of an overtraining state as well as the recovery period needed to get out of these different levels.

The spectrum goes from acute fatigue, which is the normal fatigue caused by a very intense/demanding workout, right up to a true overtraining state. In all my life, I’ve seen two cases of real overtraining. In both cases this happened to two high level athletes right after the Olympic Games (accumulation of the super intense training, the stress of qualifying for the Olympics, and the stress of the Olympics themselves).

Understand that most international level athletes will train close to 30-40 hours per week. Obviously not all of that is spent in the gym; they also have their sport practice, speed and agility work, conditioning work, etc., but these still represent a physiological stress. Yet rarely will these athletes reach a true overtraining state.

How could training for a total of five or six hours per week cause overtraining? Fatigue, yes, mostly due to improper recovery management, a very low level of general physical preparation (conditioning level), or a mediocre work capacity.

To paraphrase Louie Simmons, North American athletes are out of shape. Being out of shape (low level of general preparedness or conditioning) means you can’t recover well from a high volume of work. But the more work you can perform, without going beyond your capacity to recover, the more you’ll progress. So in that regard, poor work capacity can be the real problem behind lack of gains from a program.

By continually avoiding performing a high level of physical work, you’ll never increase your work capacity and will suffer from accumulated fatigue as soon as you increase your training stress ever so slightly. Obviously, the solution isn’t to jump into mega-volume training, but to gradually include more GPP work as well as periods of increased training stress that will increase in duration and frequency over time.

Ask any of my clients �?? they must all go through four-week phases of very high volume work interlaced between phases of “normal” volume training (or even phases of low volume). And as they progress through the system, the high volume phases will become more frequent (as their work capacity improves) or last longer."

http://www.T-Nation.com/readArticle.do?id=1442461&cr=

[/quote]

That’s all very informative, but did you assume none of us knew this? It sounds like an argument over phrases.

Am I to assume that the term “accumulated fatigue” means “overtraining” on a micro scale? In either case it is possible to recover with enough rest.

Forget I used the word “overtraining”. Consider this an article of the signs of “accumulated fatigue”.